Diving in Antarctica - Signy - 1985-86

One of the main problems with diving in Antarctica in the winter in particular is the difficulty of access to open water. There's plenty of sea around, it just has this big lid of ice on it.

Having decided where to dive, it is then necessary to reach the sea

When the ice is up to about half a meter (16inches) thick a chainsaw with a long bar is the easiest way to get through it. All is well until you break through to the sea when you get showered with icy cold water for your efforts! The approach is to cut out a big square, each side being about 1m (3 feet) or more, this floats when free at the same level it before it was cut free. The next thing is to cut this single piece into 4 equal sized blocks. If the ice isn't too thick and these pieces aren't too heavy, they can be lifted out of the water to keep them out of the way. If the ice is thick enough for these blocks to be very heavy, the technique is to push them under the water and to one side using a strong pole. As they will try to float, but are unable to, they will sit stuck up against the ice out of the way.

Having cut the hole, you then mark it with a painted pole and go off to get your mates to go for a dive. The first prospect of under-ice diving is pretty daunting, even for those who done this before it needs a particular focus. I'm always reminded of a guy I met in Antarctica who like many of us, learned to dive there. However unlike most, his first ever dive was through a hole in the ice - he was pretty nervous as you can expect, but it was made worse by the dive-master getting his weight wrong, so as he slipped into the water, he immediately sank to the bottom in about 5m of water! Not something you want to experience given the choice, but a good story to tell.

Entering the water

These guys deserve a special mention, they are professional divers and here they are about to do something partly at my request that I'm really glad I didn't have to do myself. In the winter as a marine biologist I still had to carry on catching fish - in fact it was more important then than in the summer as it was far more difficult to get the fish then and far fewer people had ever caught them in the winter months or been around to record it for science. The technique was to cut two holes about 100m apart as this was the length of a standard fishing net that we used. We drove a skidoo several times between the two holes to flatten any snow and to try to make the line obvious from below. The divers tied onto lines then dropped into the water and down to about 10-15m in 50-200m depth of blue-water, they had no points of reference other than the surface and each other, they swam the 100m to the next hole under the ice, following the skidoo trail before coming back up with the line at the second hole. The line was then used to set and recover nets until the ice broke out. It always worried me that I might let go of the line and have to ask them to do this again - fortunately it never happened.

OK, so you've psyched yourself up to it, you've checked your equipment and your buddy's too, you checked and double checked the line you're tied to and it's time to go beneath the surface.

In reality of course, what is in your mind is far worse than the reality as when diving you hardly ever go back to the surface other than at the start and end of the dive, but when this entry/leave point is focused on a small square cut in the ice (that conceivably you could lose sight of), it focuses the mind somewhat. Notice the floating ice in the hole, dive holes would usually start to re-freeze between dives, but as long as they are visited regularly, they can be easily kept open with an axe and something to fish the broken up ice out of the hole with.

Mate at surface hangs onto life-line

The key when diving under ice is to have someone at the surface on the other end of the line. There is a series of signals, pulls on the line to say "feed out", "take in" or "s**t! - drag us back now!" The line should be kept taught enough to pass signals, but not so taught as to make movement difficult for the divers and in an emergency the man at the surface could pull both divers manually back to the surface. For the line man it is a dull, and usually very cold (especially for the hands if you hadn't brought the right mitts for the wet rope) but a very important job that you can't for a minute stop concentrating on. The fact that on another occasion, we would be the ones under the ice concentrated the mind very well and helped to give the divers confidence in their mate at the surface. There is also the fact that under-ice diving is FANTASTIC! so who cares about the extra effort if you get to do something so great.

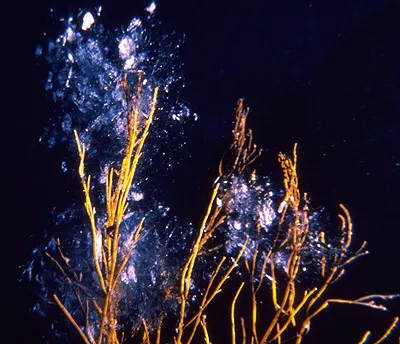

When you get to dive under ice it is to normal diving what normal diving is to swimming on the surface. I won't pretend I wasn't more nervous on these dives, but they were really unworldly and a fabulous experience. Your bubbles rise and stick against the underside of the ice making great silver mirrors as they do so. The dive hole that you worry you will lose before you go down becomes a great search-light shining down from the surface. You see things in the water in these winter conditions that you never see otherwise, in this picture for instance, I'm swimming through a huge swarm of sea-creatures related to jellyfish called "Ctenophores" you can make out 3 of them oval-shaped objects behind me in the picture. There were literally thousands of them drifting slowly by, most are not visible in this picture. Ctenophores have bands of cilia that run their length and waft them along causing interference patterns as they do so, this looks like a monochrome world, but in reality I was surrounded by numberless rainbow phantoms.

The sometimes eerie world of diving has entered an new dimension

Just got into the water and ready to go down - I'm already down to take this picture :o) Note the ice blocks that have been cut to make the dive hole stuck up against the ice, these are pushed under the ice with a pole as they're too heavy and difficult to get out of the dive hole. This kind of diving is really like entering another world, more so than anything I've ever done. A great thing to do at the end of a dive when you have a little air left is to go up to the dive hole and take off your weight belt. You're then very buoyant and so can go back under the ice and walk around upside down on the underneath of the ice, if you lose your footing, you fall - up! Highly recommended to anyone who has ever thought about walking on the ceiling.

When the temperature drops in the sea, sometimes in the shallows ice starts to form below the surface as it is here. It starts as a nucleation point which can happen on submerged sea weed as here as delicate flakes of ice randomly forming ice crystals. In the shallows of 1-2m, ice may form on the sea bed from below as above. Normally ice freezes from the surface of the water down as ice has a very unusual property amongst all substances in that as it turns from liquid to a solid, so it expands rather than contacts which is normal for cooling materials. This is why sea-ice floats rather than sinks as it would if it was almost anything else. The effect on the planet is profound, if water behaved "normally" then the oceans would be mainly solid ice other than the upper reaches and warmer climates. Water has its maximum density at 4C and so all of the depths of the worlds oceans are at or around 4C as this temperature water descends due to it being denser than water around it of other temperatures.

Things to see under the ice

The Antarctic Ocean is unique amongst the worlds oceans in that it has hardly any decapod crustaceans - crabs and lobsters that are found in abundance in the rest of the world have never crossed the Antarctic Convergence, so their role is taken by other organisms of which this is one, Antarcturus signiensis. It has only been so far found in and around Signy Island and the South Orkneys where it is regularly encountered on dives down to 25m. There are a whole host of organisms that take the place of Decapod crustaceans in Antarctica, many of which display signs of gigantism compared to their relatives elsewhere in the world. Underwater in Antarctica is a place where entirely new species to science may be encountered.

What's the Viz? - It's how far you can see underwater. How many times did I hear that? In the winter in Antarctica, sea-ice forms and kills the ocean swell, this stops water movement stirring up any sediment in the water column which then settles out. After a few weeks, the visibility rises to a distance that is pretty much unknown in any other circumstances. I recall seeing an horizon under water. The best "Viz" was at the end of winter when the sea hadn't been stirred up, but there wasn't a light-stopping ice layer, so you could see clearly through the water and there was plenty of light to see with. What's the Viz? 30m - 50m?, the optical effects of the water then started to take over - but effectively it was as far as the eye could see. Oh yes - sitting on an ice berg at about 15m in this shot and seeing how far I could see.

Diving on an iceberg - amazing at first...

Diving on an ice-berg, what an ethereal experience! Well, yes it is in an "I've done that" sort of way, but actually it gets a bit dull beyond the first five minutes or so when you've taken the pictures of each other. The berg is either no threat to at all - it just sits there as a massive presence, like an underwater building, or there are a number of large "bergy bits" separate, but close and potentially moving. In that case, they are probably ok, but you're not sure and you certainly don't want to get stuck between a couple of pieces of ice that easily weigh 100+ tons each. I've also dived on bergs that are all sort of big crevasses and small caverns underneath which were dark and spooky and scared me in case I ended up up inside them and forgot how to get out again - this was more in my mind than reality, but I considered it a survival instinct worth listening to. Diving on an ice-berg? do it once, get the pictures and don't bother again as it's actually a bit dull.

A diver prepares to swim under ice and lay a line so that fishing nets can be laid. The ice wasn't so thick here as can be seen by the blocks that have been able to be lifted out of the hole rather than pushed underneath the ice. If they are under, there's a chance the rope can get caught on them, more of an annoyance than a danger, but worth avoiding if you can. There's something very odd about going diving like this, get kitted up, sit on the sledge behind the skidoo, drive out to the hole and turn the engine off. Instant silence, no water to be seen until you break the hole open again, no movement at all, for a moment you wonder if you've got this right and didn't just get kitted up by mistake...

Into a different world

Emerging from a dive in Antarctica is like emerging from a dive anywhere else except more so. The underwater world of rocky faces and ledges can be as vividly coloured as anywhere in the world, brightly coloured encrusting invertebrates with shells and fish. It's also not too cold thanks to what you're wearing, and under the ice it is of course all perfectly still, no waves, no swell. Back on the surface the world becomes black white and blue again and all your diving gear weighs more than ever as you've extra weights to keep you down against the extra buoyancy of your suit, a result of it's extra insulating abilities.

On nicer days you could dive somewhat further afield, the limiting factor was how long it took to get back to base after the dive while you were wet. The water was around -2C (around 28F) and ok in your wet suit, but once out of the water, you had temperatures that could be far below this and windchill to deal with too.

Usually it's a case of get there, dive and straight back to base again.

All the diving at Signy base at the time I was there was done using unlined close-fitting wetsuits, long john and then a top with integral hood, boots were similar and hands were enclosed in mittens. With your mask tucked under the top part of your hood, the only exposed flesh was cheeks and lips - and I recall seeing some very blue lips while underwater on dives! There was a collection of wetsuits on base, most of which had been made to fit the professional divers and then left behind to be used by others when their tour was done. These guys in the picture are both professional divers and they have the luxury of 10mm wetsuits that were made to fit them. I amongst others was a marine biologist, but not a professionally trained diver (I had never dived before I went to Antarctica) and so had to make do with a 6.5mm wetsuit and 4mm vest underneath it. getting in and out of these wetsuits was a 2-man job, but the close fit meant that there was minimal flushing of water and maximum insulation value. The problem with such thick wetsuits though was that they were very buoyant requiring extra weights to stay down and more attention to buoyancy if your dive-profile varied up and down much during the dive. On the other hand, the cold water was it's own safety device in that you couldn't really stay down for much beyond 30 mins at depths below 10m as you got cold. The neoprene compressed more the deeper you went and so you got colder quicker! It was the cold that usually brought you back out of the water. The longest dive I remember was a fishing dive using small hand nets at around 3-7m, when I stayed down for about 50mins and felt like a block of ice when I came out!

Struggling out of the water at the end of a dive. This diving was in the days before all-in-one BCD's (buoyancy control device) that are put on like jackets, instead a separate ABLJ (Adjustable buoyancy Life Jackets) were worn with separate back-packs to hold the bottle, ABLJ,s had a small air bottle separate from the main air supply and could be breathed from in an emergency You may also notice that the demand valve is twin hose and not single hose (octopus rigs were still extreme exotica, not to become the norm for a good many years). Twin hose rigs had the advantage of being far less prone to icing up in extreme cold conditions and so were used pretty much exclusively in the winter and certainly on under-ice dives. Single hose valves had a tendency to ice-up and free-flow when it got very cold, they could be used without problem in the summer months when sea temperatures rose to maybe +1 or +2C, from the -2C of winter, but the small difference was enough. These days, the technology has progressed and low temperature single hoses are far more reliable.

Check there's no seal to land on and in you go

Before getting into the water a check needs to be done in case there's a seal around that might just be on its way up for air. One guy I knew had a seal pop its head up at his feet when he was just about to slip into the water! That never happened to me unfortunately, but I did see seals appear when I was being a line man and the divers were down and in particular when we'd just broken the ice on a hole to set a fishing net - they were more common in the deeper water where we set nets than the shallower areas where we'd dive. Seals were reputed to be more approachable with the twin hole demand valves we had as the bubbles come out from the unit which is attached to the tank behind you head and not from your mouth. They are a bit harder work than single hose units (have to suck more) but it was nice not to have bubbles going past your face all the time.

Here's a happy group of divers returning from a fantastic dive, wonderful viz, bright sunshine, totally calm water conditions and an underwater world that is as colourful as the one of the surface is monochrome.

This picture also reminds me of the emergence of some kind of group of (happy) creatures from the Black-Lagoon.

The scenery is pretty good too when you come out too!

This has to be pretty much ideal diving conditions in Antarctica. You can walk to the dive site from the dive store where you kit up, the ice edge is over an area a little way out from the shore, so no swimming to get where you want to be. There's newly formed slushy ice at the edge of the older ice, so any sediment in the water has fallen out to give truly amazing viz, but the new soft ice is easy to break through, keeps it calm and also lets plenty of sunlight through.

Not every dive was in good conditions! This is me (right) and my mate Paul (left) having come back after a dive about 200m away. The ice in the sea meant we couldn't take a boat or swim at the surface, the snow on land was too deep to walk through, we found that we were too light on weights (all that neoprene makes you very buoyant) to get down and under the ice in 2-3 metres, so we decided to wade through the ice along the inshore shallows to where it was deeper and then force our way through to about 5m and dive down. It was incredibly hard work to get out there, then finally we were ready to dive down and I in particular kept bobbing back up like a cork. To stay down I had to get deep enough for my suit to be compressed and so not be so buoyant as to take me back up to the surface again. I was concentrating on this so much and finning like buggery to get myself to sink that I neglected to clear my ears soon enough - no time to pause, I'd just pop back up again.

We did get down and have a decent dive, but we had to wade through all this very heavy slushy and lumpy ice again and that ear-clearing episode that I forgot about meant I perforated my right ear drum. We were so knackered and probably bad tempered when we finally got back to the base, that someone felt they had to record it for posterity, so here it is! The ear-perforation was painful - like ear ache (unsurprisingly) when the doctor checked it, he said it was about as tiny a perforation as it was possible to ever have. It cleared up after a week or so and has never caused any problems, it taught me a lesson though, and I suggest you don't try this at home!

Time for just one more dive if we can find some water that is

And so the diving goes on. The first reaction of people when I tell them I dived in Antarctica is one of horror, so cold and then you voluntarily get in the water! Well, I've heard more than one person say that they've been colder while diving in the UK than they ever were in Antarctica, like everything else there, as long as you are properly equipped and take all precautions, there's no reason that it shouldn't be perfectly safe and enjoyable. We were lucky on the base I was on to be able to dive recreationally, and in particular I was lucky as a marine biologist in that I got to do it more than most people.

I'm afraid I don't have pictures of them, but my best Antarctic dives ever weren't under ice or even in fantastic viz, they were in about 3-10m of water while surrounded by southern fur seals. The fur seals would swim through the sea, hear your bubbles at a distance and swim over to find out what was going on. Before long, you would be diving with a small group (2-6) of very playful seals that would start by "hanging" from the surface, tips of their hind fins just out of the water while they looked you in the eye, sometimes from very close quarters. They would then dive down and swim around you, sometimes "mouthing" your fins with their teeth (nothing else to feel them with) and generally as curious about the divers as the divers were about them. I remember a seal swimming a circle around me and swimming faster than I could spin on the spot with all my gear on to keep up with him.

Diving on an ice berg is a nice "done that" thing to tell people, but for a truly memorable and remarkable experience, I'd dive with fur seals any day.