Shackleton Endurance Expedition

1914-1917 - Trans-Antarctica

3 - The James Caird

1 - departure |

2 - trapped and crushed | 3 - this page, journey

to South Georgia |

4 - rescuetime-line & map | crew of the Endurance | the Ross Sea Party

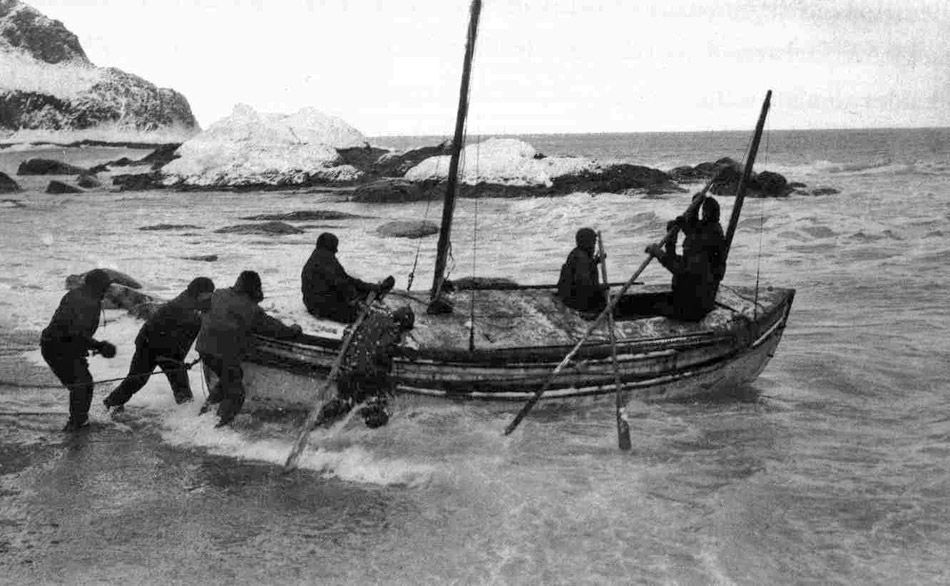

The voyage of the James Caird, all but 6 remain on Elephant Island hoping the 6 that set off can bring about a rescue

The James Caird, the lifeboat that was

in best condition, patched up and partially decked

over by what meagre resources were available sets out on a rescue

mission to South Georgia

The James Caird set off on the 24th of April 1916 on a day of relative calm, the very last day before the pack closed in again around Elephant Island. The crew was Shackleton, Worsley, Crean, McNeish, McCarthy and Vincent, the anticipated journey time was a month. It was to become one of the most astonishing small boat journeys of all time

Those

remaining on Elephant Island bid farewell to the six setting

Those

remaining on Elephant Island bid farewell to the six setting

out in the James Caird to reach South Georgia

The James Caird made progress at the rate of around 60-70 miles per day through rough sea conditions. The sea constantly came in and made everything including the sleeping bags wet, it was difficult to find any warmth at all. There were four sleeping bags made of reindeer hide which shed their hairs in the constant dampness, making them less effective and clogging the pump used to empty the sea water that spilled over into the boat.

The boat was relatively light and so boulders and other ballast had been placed aboard in order to trim her, these had to be constantly moved around. The weather worsened and they encountered fierce storms, As the temperature dropped, ice formed on the outside of the boat from frozen sea spray, up to 15 inches deep on the deck. This made the boat much heavier and affected the trim - more moving around of boulders - the men also tried as far as they could to chip away the accumulated ice with any tools that they could improvise, though the situation worsened. They began to throw items overboard in order to save weight, the spare oars went as did two sleeping bags that by now were soaked through and hard and heavy with ice.

At other times they had to bale out water for dear life, the only solace during this journey were hot meals every four hours by the light of a primus stove.

They had been drifting for some time under light sail held back by the sea anchor due to the sea state (a sea anchor is a sort of large canvas bag that acted to slow the boat and prevent it from being tossed around quite so violently during stormy seas). The sea anchor however was lost as the boat fell into a large trough between waves and the men then had to beat the canvas sails free of ice and set them again properly in order to keep on course.

Frostbite affected exposed fingers and hands in the cold and constant wet. Navigation was a problem due to the continually overcast weather. On the seventh day at sea however a break in the cloud came and Worsley was able to take a reading from the sun, six days since the last observation, he calculated that they had traveled around 380 miles and were almost half-way to South Georgia. The short period of sunshine meant that the men were able to spread their clothing and other gear over the boat deck and the mast to dry out. The ice became less dense and they occasionally were accompanied by wildlife, porpoises and tiny storm petrels.

The voyage of the James Caird.

Mountainous seas in the southern ocean made this one of the

most incredible small boat journeys of all time.

On May 5th, the eleventh day out at sea,

the sea became much rougher, Shackleton was at the tiller:

"I called to the other men that the sky was clearing, and then a moment later I realized that what I had seen was not a rift in the clouds but the white crest of an enormous wave.

During twenty-six years' experience of the ocean in all its moods I had not encountered a wave so gigantic.

It was a mighty upheaval of the ocean, a thing quite

apart from the big white-capped seas that had been our tireless

enemies for many days. I shouted 'For God's sake,

hold on! It's got us.' Then came a moment of suspense

that seemed drawn out into hours. White surged the foam

of the breaking sea around us. We felt our boat lifted and

flung forward like a cork in breaking surf. We were in a

seething chaos of tortured water; but somehow the boat lived

through it, half full of water, sagging to the dead weight

and shuddering under the blow. We baled with the energy

of men fighting for life, flinging the water over the sides

with every receptacle that came to our hands, and after

ten minutes of uncertainty we felt the boat renew her life

beneath us"

On May 7th Worsley again was able to take a navigational reading and reckoned that they were not more than a hundred miles from the northwest corner of South Georgia, another two days with the wind with them and they should have the island within sight. On the morning of the 8th of May, they began seeing kelp floating in the sea, then some sea birds, just after noon they caught a glimpse of South Georgia, only fourteen days after leaving Elephant Island and about half as long as they thought the journey would take.

Landing was to be a less than straightforward affair, reefs (shallow rocks just below the sea surface) stretched all along the region of the coast where they were and great waves broke over them. The rocky coast in many places descended steeply into the sea. Despite being so close and running out of fresh water to drink, they had no choice but to wait for the next morning to break before attempting to land on the shore.

The morning brought a shift in the wind and a terrible storm arose, the James Caird was tossed around in the sea and when light broke, they were out of sight of land once again. They made their way back to South Georgia just after noon, but again, it was a coast of huge breakers and sheer cliffs that greeted them. The day wore on and there seemed no hope, later though in the evening, the wind shifted direction and began to die down. By the morning of the 10th of May, there was very little wind and they were able to look for a landing place. Reefs and breaking waves dogged their every attempt. They found a likely bay, but were blown out to sea again by a change in the wind. In approaching darkness they eventually were able to enter a small cove fronted by a reef, they had to take in the oars to pass through, but at long last, carried by the swell, the James Caird was able to land on a South Georgia beach at King Haakon Bay.

They had got through thanks to Shackleton's leadership and the incredible navigational skills of New Zealander Frank Worsley. Worsley had only been able to take sightings of the sun four times, on April 26th and May 3rd, 4th and 7th, all the rest had been dead reckoning, keeping on the same straight line in the same heading.

Had they failed to land, the boat would have been swept onwards to be lost in the mid Atlantic, and no rescue party would have set out for the men on Elephant Island.

King

Haakon Bay, South Georgia, hauling the James caird

up the shore across grounded brash ice (composite photograph

and drawing)

King

Haakon Bay, South Georgia, hauling the James caird

up the shore across grounded brash ice (composite photograph

and drawing)

Next page: Crossing South Georgia and rescue from Elephant Island

Picture credits, copyright pictures used by permission: Point Wild Glacier - by David Stanley from Nanaimo Canada, used under Creative Commons 2.0 Generic license.

Ernest Shackleton Books and Video

South - Ernest Shackleton and the Endurance Expedition (1919)

original footage - Video

Shackleton

dramatization

Kenneth Branagh (2002) - Video

Shackleton's Antarctic Adventure (2001)

IMAX dramatization - Video

The Endurance - Shackleton's Legendary Expedition (2000)

PBS NOVA, dramatization with original footage - Video

Endurance : Shackleton's Incredible Voyage

Alfred Lansing (Preface) - Book

South with Endurance: Frank Hurley - official photographer

Book

South! Ernest Shackleton Shackleton's own words

Book

Shackleton's Way: Leadership Lessons from the Great Antarctic Explorer

Book