British Antarctic Expedition 1898 - 1900

Carsten E. Borchgrevink

- Southern Cross

The Crew Alphabetically

Andersen, Johan A. - Able seaman

Anderson, Lars (48) - Steward

Been, Carl H.J. - Fireman

Bernacchi, Louis Charles (24 - Australian)

- Astronomer / Physicist -

W

Bjarko, Oscar M.

- Able seaman

Borchgrevink,

Carsten E. (34 - Norwegian) -

Expedition leader

- W

Brynildsen,

Karl - Fireman

Colbeck, William

(27 - British) - Magnetic observer / cartographer

- W

Ellifsen, Kolbein (23) - Cook -

W

Evans,

Hugh Blackwall (23 - British) - Assistant

zoologist - W

Fougner, Anton (30 - Norwegian)

- Scientific Assistant -

W

Hansen,

Hans (21) - Second mate, Experienced ice navigator

and hunter.

Hanson, Nicolai

(28 - Norwegian) - Zoologist -

W,

the first known death on the Antarctic continent

on the 14th of October 1899, he had been ill since

July with what is thought to be beriberi.

Jahnsen, Johannes - Cook

Jensen, Bernhard - Captain

Johansen, Alex - Ordinary seaman

Johansen, Julius - second engineer,

professional engineer at Jensen and Dahl shipbuilding

yard, Friedrikstad, Norway at the time of appointment

to the expedition..

Johnson,

Hans J. - Able seaman

Karlsen,

Adolf M. - Ordinary seaman

Klemetsen,

Klemet - Boatswain

Klovstad,

Herlof (30 Norwegian) - Medical Officer -

W

Larsen,

Lars A. - Able seaman

Larsen,

Olof - Able seaman

Magnussen,

Franz Johan - Able seaman

Must,

Ole - Doghandler -

W, a

Finnish Laplander, born 1877, like Savio, an experienced

snow-shoe runner.

Olsen, J.

Christian - First engineer, first class certificate,

professional engineer at Jensen and Dahl shipbuilding

yard, Friedrikstad, Norway at the time of appointment

to the expedition.

Petersen,

Jorgen - First Mate

Samuelsen,

Ingvard - Able seaman

Savio,

Persen (21) - Doghandler -

W, a

Finnish Laplander, "well known for his faithful

character, hardihood and intelligence."

Ulis, Hans - Carpenter

W -

Wintered

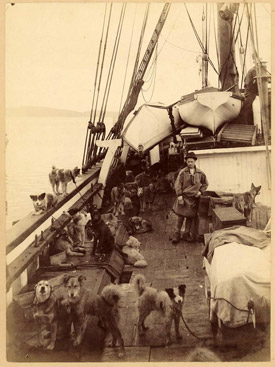

SS Southern Cross in the Derwent River, Hobart

Tasmania 1898, before leaving for Antarctica

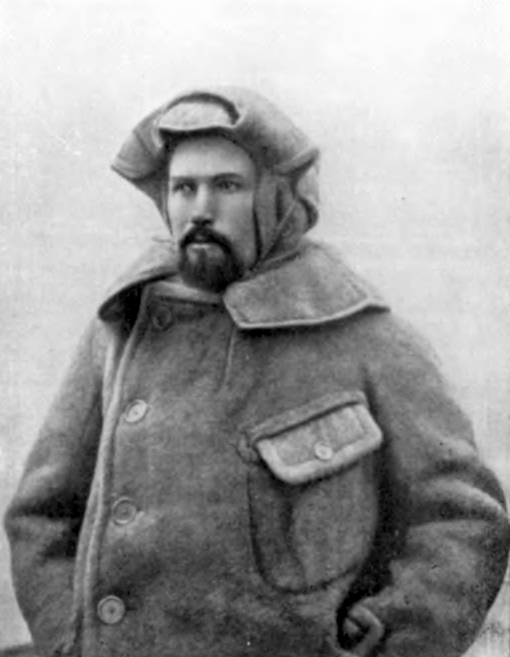

Carsten Borchgrevink was an ambitious Anglo-Norwegian living in Australia who had previously sailed to Cape Adare in the Ross Sea region of Antarctica on a Norwegian whaling expedition. In January 1895 he was one of the first men to indisputably set foot upon the Antarctic continent, there are earlier claims going back to 1821, but these are unverified. That he was one of the first group was indisputable, his claim that he was the first was disputed by two other men, Leonard Kristense and Alexander Tunzelman who each claimed that they were the first.

Following this he considered that it was feasible to over-winter at Cape Adare, he arranged funding from a wealthy London publisher and so what became the "British Antarctic Expedition" was born, despite the fact there were only three British nationals amongst the largely Norwegian crew.

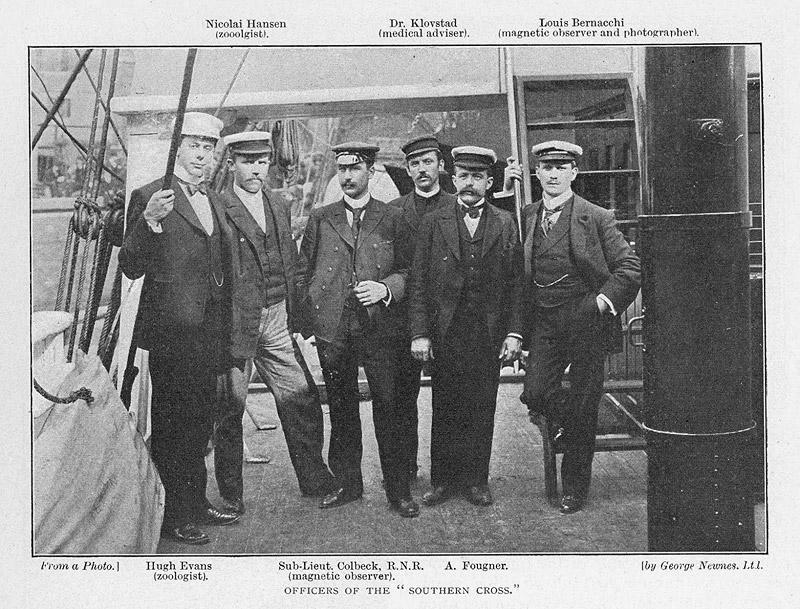

Officers of the Southern Cross

The expedition ship the "Southern Cross" left for Antarctica via Hobart, Tasmania with 90 sled dogs and a disparate crew of 31 men of varied nationalities. They reached the Ross Sea on the 31st of December 1898, and took 43 days to get through the pack ice, at one point a gale pushing the ice raised the ship by 4 feet. The ice was composed of some large slabs which allowed the dogs to be exercised by running across it and the crewmen to practise on skis.

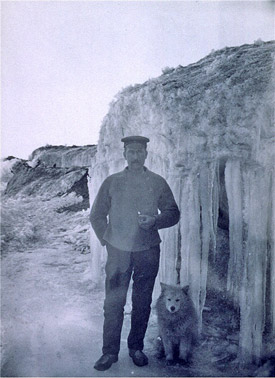

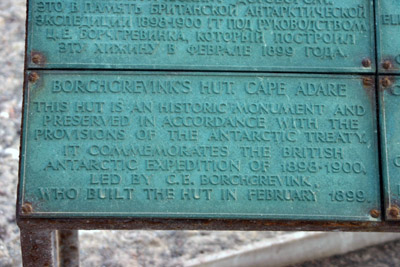

The ship reached Cape Adare on the 17th of February 1899, work began to move stores ashore and build a hut for the ten winterers to live in for the next year, Borchgrevink called the site Camp Ridley after his mother.

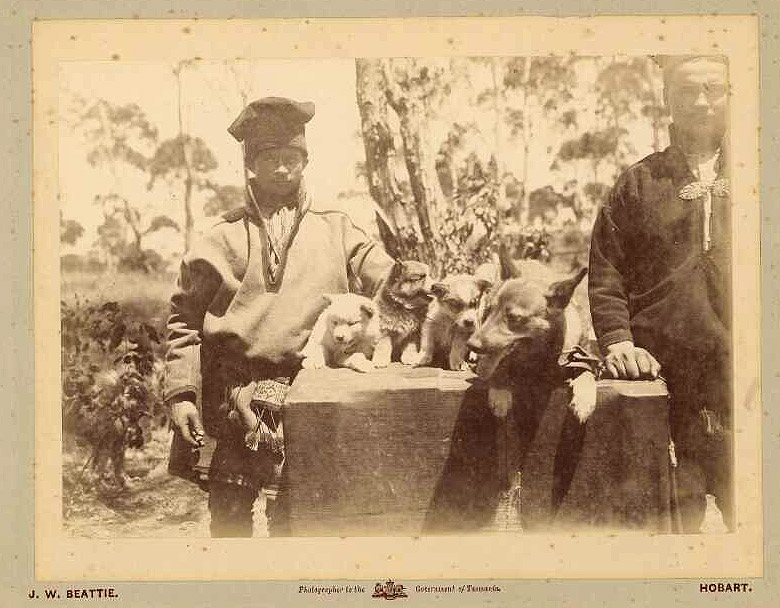

Per Savio and Ole Must, Doghandlers, Finnish Lapps in Hobart Tasmania prior to going to Antarctica

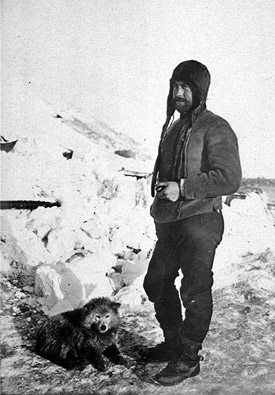

Seventy five dogs were taken ashore, the first time dogs had been used in Antarctica. Things didn't go smoothly, the whole expedition came close to being lost when during a four day long severe blizzard, the Southern Cross lost its anchor, the engines alone kept it from running aground. Seven men were stranded ashore at the time, provisions had been only partially unloaded from the ship, though fortunately they had a tent and survived by bringing in the dogs to lie on them for warmth.

When the ship sailed to winter in the north on the 1st of March 1899, the wintering party of ten men at Cape Adare became the most isolated people on earth.

Two huts were erected, they were 5.5 x 6.5 metres (18 x 21ft), one was the living quarters and the other was used for storage. The accommodation hut had (has - it is still stands) 2 small rooms off the entrance porch and then a large communal room. Five sets of bunks beds around three of the walls gave each of the ten men a little privacy and sleeping space while the rest was available for all with the stove providing cooking facilities and heat.

The combination of nationalities and social positions would have made for somewhat uneasy relations at the best of times but were particularly difficult in these cramped conditions where severe weather sometimes kept all of the men indoors for days on end. This was the first Antarctic Winter spent in the manner that was to become the pattern from that point onwards up to the present day.

Many lessons on how-to-winter were learned, many of them the hard way. Draughts made the hut cold to begin with, so these were blocked which later led to near asphyxiation of some men from carbon monoxide poisoning as a result of the lack of ventilation. Excessive heat was a problem when the stove was burning for cooking. At one point a fire from a candle left burning in a bunk scorched one wall of the hut, this led to Borchgrevink assembling survival provisions and tents in case another fire should leave them without shelter, food and equipment, months away from the next ships visit.

As the winter approached so the animals around the hut disappeared, seals, penguins and other birds went north to escape the severe Antarctic winter. The men settled into activities and routines of meteorological and magnetic observations, the collection of biological and geological specimens and surveys along the coast.

Borchgrevink had anticipated that a winter at Cape Adare would not be too difficult, the reality was not as easy as he anticipated, dog kennels blew out to sea, a boat was lifted and smashed by the wind, the wind vane and anemometer were destroyed by the very strength of the wind they were trying to measure. Several of the men had life and death near-misses when away from the hut due to changing weather and sea-ice conditions.

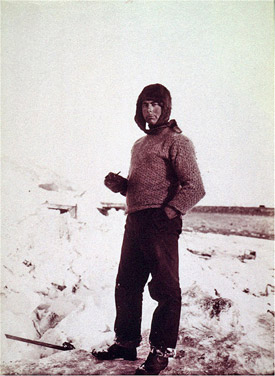

Per Savio, a Finnish doghandler had a particularly unpleasant and very dangerous experience when he fell un-roped 60 feet down a crevasse becoming wedged head-down, another two feet to one side and he would have been lost in the deeper void of the crevasse. He could hear his companions above, but they could not hear him, eventually he regained his composure, leaned his back against one wall of the crevasse and cut toe-holds with the aid of a pocket knife he just happened to have on him in the other crevasse wall, he eventually climbed the 60 feet and emerged exhausted, very shaken and unable to speak.

The depths of winter with no light, not even twilight, colder temperatures and worse weather confined the men to the small hut interior where they did their best to pass the time and get on with one another in the confined circumstances. On the 30th of June a sled dog retuned to the hut, it had been lost five weeks earlier after being blown out to sea on an ice floe, it was apparently well nourished and in good spirits demonstrating the ability of sled dogs to survive in the harsh Antarctic environment, even at the worst time of year.

Nicolai Hanson a Norwegian zoologist became ill during the winter, he worsened rapidly in October and on the 14th requested to see each expedition member individually to say goodbye and shake hands, he chose his own burial spot at the summit of Cape Adare. 30 minutes before he died, the first Adelie penguin of the summer season appeared and was brought to him when it is reported that he took great delight in seeing the bird in his final moments. He was officially diagnosed by Klovstad the doctor as having died of "occlusion of the intestines", though his symptoms point to beriberi caused by a dietary deficiency of thiamine resulting in heart failure.

Nicolai Hanson

At the summit of Cape Adare the ground was frozen and had to be excavated with dynamite, a service was held and the Finns sang.

Soon the end of winter was signified by the animals returning in ever greater numbers, penguins were taken for their meat and eggs. The ship was expected to return from late December onwards, though there was no sign of it well into January and the winterers began to feel concerned. On the 28th of January 1900, the ship arrived early in the morning, only Ellefsen the cook was awake, Captain Jensen of the Southern Cross entered the hut calling "Post" and drooped his mail sack on the ground, the sleepers all awoke and realised their isolation was over. Theirs was the first ever wintering party on land in Antarctica.

On the day they left the hut, Louis Bernacchi wrote in his diary:

"May I never pass another 12 months in similar surroundings and conditions."

The expedition was not yet over and over the next two weeks before heading north, the ship visited several locations in the vicinity making a number of landings, most notably on the 16th of February when the first landing was made on the Ross Ice Shelf at the Bay of Whales (alternatively known as Borchgrevink's Inlet or Balloon Bight), at this point the Great Ice Barrier is only a few feet above sea-level. Dogs, sledges and provisions were landed and Borchgrevink with Colbeck and Savio reached 78deg 50' South, the furthest reached at that time.

On the 10th of February Borchgrevink and Captain Jensen narrowly escaped drowning on the coast at the foot of Mount Terror. Alerted to a 15-20 foot high wave produced by the calving of an ice berg they quickly got as high up a nearby hill as they could and clung onto the vertical rock while the wave washed over their heads followed by several smaller waves to chest height.

On return to England the reception Borchgrevink received for his privately funded expedition was poor, particularly from the establishment and the Royal Geographic Society who had been preparing their own expedition before he left, this would become Robert Falcon Scott's Discovery Expedition. The range of nationalities of those involved led to the "Britishness" of the expedition being seen as somewhat dubious.

Borchgrevink's accomplishments were extensive, though it wasn't until more than ten years later when Scott's Northern Party wintered at Cape Adare in 1911/12 that the difficulties he had faced and overcame were acknowledged. His team had made many scientific observations and discoveries, the expedition had made many first landings in a number of locations, they had achieved a new farthest south and had discovered a way of gaining access to the Ice Barrier that would be used by Amundsen on his journey to the South Pole.

Borchgrevink embarked on lecture tours in England and Scotland and was eventually made a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. In 1902 the American Geographical Society held a dinner in his honour. Norway made him a Knight of St. Olaf and then a Knight Daneborg. In 1930 the Royal Geographical Society awarded him the Patron's Medal of The President and made a statement:

"When the Southern Cross returned, this Society was engaged in fitting out Captain Scott to the same region, from which expedition much was expected, and the magnitude of the difficulties overcome by Borchgrevink were underestimated. It was only after the work of Scott's Northern Party on the second expedition of 1912 . . . that we were able to realise the improbability that any explorer could do more in the Cape Adare district than Mr. Borchgrevink had accomplished. It appeared, then, that justice had not been done at the time to the pioneer work of the Southern Cross expedition, which was carried out under the British flag and at the expense of a British benefactor".

Evans, Hugh Blackwall (23 - British) - Assistant zoologist

Hugh Blackwall Evans later resided in my hometown of Vermilion Alberta. Each year he would be invited to speak to to school children about his experiences while part of the expedition. I was about 12 years old when I first heard him speak of his experiences in Antarctica and in ensuing years had further conversations with him. He was a well known and respected local figure.

He is buried in the Vermilion cemetery.I understand he was invited to be a member of the second Scott expedition at the last minute and did journey to New York in order to meet a ship. He missed the connection because of problems with railway schedules and a tight time line. He had been contacted by telegraph while in Vermilion and had to quickly postpone either wedding or engagement plans.

He did admit that in hindsight he was fortunate to have "missed that boat" because he may then have been involved in the later less fortunate expedition. He seems to have spent most of his time on the ship while it was locked in the ice. The crew had a full daily schedule of duty involving recording temperatures of air and water and of using an under ice net to sample fish and sea life. New species were recorded and then cooked and eaten by individual crew men to determine if they were safe or edible.

I recall him saying that to a British sailor "there was little that was not edible."

Anthony Dixon.

Pictures courtesy - Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania.